If you didn’t know, the World Health Organisation (WHO) gets its funding in two ways:

- Its member states (MS) are committed to pay WHO assessed contributions(ACs), the amount being determined by that country’s wealth and population (i.e. the United States pays more than Tuvalu);

- MS also pay voluntary contributions, as do a bunch of non-states actors (NSAs), the most generous of which is the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

ACs are predictable (by signing up to the WHO, MS commit to paying a fixed amount every biennium) and flexible (the WHO is free to do what it likes with the money). VCs are voluntary, ranging from a bit flexible (WHO can choose which category of its work gets the money) to not at all flexible (the money has to be spent on whichever health issue the donor specifies).

In short, ACs are ‘quality’ funding; VCs are a pain in the ass. Unfortunately, most of WHO’s budget comprises of VCs – 80% of it in fact.

WHO knows this, and it also knows that wealthy MS have, historically, funded certain health issues and neglected others. So when the WHO Secretariat draft WHO’s budget, they start to think strategically. When you read the WHO’s programme budget 2018-19 and also Director General (DG) Dr Tedros’ reflectionson it, a process emerges. Here’s Tedros:

“Ten programme areas receive 80% of all specified voluntary contributions. Fourteen programme areas receive less than 2% of the overall specified voluntary contributions; that means that they do not attract sustainable voluntary specified funding necessary to achieve the Programme budget results” (Para. 9)

Now follow that with a couple of paragraphs from the actual, approved, budget:

“Budget adjustments are made in areas that continue to attract less donor interest” (Para. 13)

Specifically, in the case of non-communicable diseases (Category 2 of the budget):

“Based on the experience of past bienniums, on average only 60% of the budget for these programme areas in category 2 is funded in each biennium. More than half that funding comes from flexible resources (core voluntary contributions and assessed contributions)” (Para. 32)

And finally:

“This funding reality has encouraged a strategic shift towards a more catalytic role of headquarters and regional offices to support countries in scaling up interventions to deal with non-communicable diseases and to seek new ways to strengthen inter-sectoral collaboration in the context of the Sustainable Development Goals” (Para. 32) [emphasis added].

When academics talk about donor influence over the WHO, it’s often difficult to pin down. But here you have it, in black and white: donors fund x but not y; WHO knows that, thinks strategically and drafts a budget that reflects those donor preferences; there is an anticipated shortfall in funds for y; WHO changes its behavior (its HQ and ROs become ‘catalysts’, they seek ‘collaboration’ (read partnerships with NSAs i.e. industry); and they get behind whatever development fad is en vogue(the SDGs, for example). When you spell it out like that, and then hear Tedros address MS with pep talk platitudes like “don’t accept the status quo” (closing address at WHA 71) you can’t help but wonder who he’s kidding.

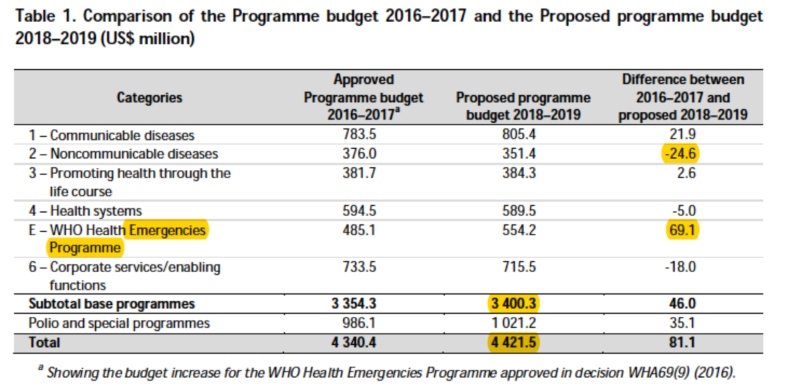

But let’s take another look at Polio. The screenshot at the beginning of this post is taken from WHO’s new budget portal. Credit where credit’s due, it’s a pretty cool piece of work. Well done WHO! It shows what we’ve known for a few years now – polio is awash with funds ($US902.8m to be precise, delivered through the Global Polio Eradication Initiative). That money appears as part of the ‘Polio and special programmes’ line in the table below. It’s funded solely from VCs, with the US and the Gates Foundation GPEI’s primary funders (the US provided $106m for 2017; Gates $95m). Gates has pretty much bank-rolled the polio eradication programme, with grants to WHO of $682m in 2008, $84m and $50m in 2011, and $204m in 2013).

There’s a push to rid the world of polio: it’s a crippling disease and it would be a major global health victory if it was eradicated. But it’s not the only global health problem, the last stages of eradication are the hardest to justify financially and ethically, and there comes a point – now in fact – when the WHO has to consider winding down the initiative.

WHO’s action plan for polio transition was considered and approved by MS at the WHA last week. Unsurprisingly, many MS were worried about what happens to polio when the VCs are scaled down. MS are not the only ones who are worried – WHO auditors are too. They’ve put polio funding in their top three highest risksfacing WHO in the coming years, presenting a risk “to programmes or offices most dependent on polio funds; financial liabilities associated with the fixed term staff of those programmes; and potential delays to the timely eradication of polio”.

But there’s another cloud on the horizon, and it’s dark. Take a look at the photo above, shared via Ilona Kickbusch on twitter, of a slide presented at the Graduate Institute last week in Geneva. It shows WHO anticipates that it will have to cover ongoing polio costs from its core budget should VCs dry up (in case you can’t read it, bullet 5 reads: “These costs will be moved to the WHO’s core budget”. I bet you’d like to know what WHO’s auditors think is the number one financial risk facing WHO as it rolls out its GPW:

“Financing of the 2018–2019 Programme budget (primary risk related to flexible funding due to reduction in core voluntary contributions and uncertainty regarding future funding prospects)”

So, WHO is committed to eradicating polio; donors are fickle and unreliable; VCs can dry up; WHO’s core budget is fixed; if it has to tap into it to cover gaps in polio funding, it’s going to put even more stress on its miniscule budget. There’s a storm brewing, Dorothy!

All of this would matter so much less if WHO got loads of money from its donors. But it doesn’t. Remember, its budget for 2018-19 is just US$4421.5m. That sounds like a lot but as David Legge from the People’s Health Movement has pointed out:

“An annual budget of around $2,200 million… is around 30% of the annual budget of US CDC; 4% of Pfizer’s turnover; 3% of Unilever’s turnover; and around 10% of Big Pharma’s annual advertising in the US. It is simply not enough for WHO to properly fulfil its responsibilities in global health”.

Questions, questions. Why don’t MS pay more? The answer to that is quite straight forward: it allows MS – and we’re talking primarily about WHO’s biggest donor the United States – to control WHO. The United States doesn’t like WHO. If you were at the WHA last week, you will have heard overtly hostile statements from the US about pretty much everything the WHO had done or was hoping to do. US ACs are fixed at subsistence levels and its VCs go wherever the US wants them to go (all US VCs are tied to specific health issues). It ensures, to quote Legge again, a “chokehold” over the organisation.

Salvator Mundi – US$450m well spent

It’s important to remember that member states could easily pay more, if they wanted to. In 2017, for example, the United Arab Emirates paid WHO US$1.4m in ACs and US$18.4m in VCs. The same year, its Ministry for Culture paid US$450m for Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi, the highest amount of money ever spent on a single painting. US$450m would pay for WHO’s entire Global Health Emergencies budget.

What’s the WHO to do? Its previous Director General Margaret Chan asked MS for a 10% increase in their ACs. After they stopped laughing and realised she wasn’t joking, the proposal was quietly dropped. Her replacement Dr Tedros had more success squeezing a few pennies out of MS, who approved a 3% increase last year – a whopping US$28.7m over two years! Alternatively, it might – and is – going down the familiar route of trying to do more with what it’s got. You know, trying to identify ‘best buys’, getting ‘more bang for the buck’, in the hope that by demonstrating efficiency MS will be more inclined to trust the WHO with more flexible funds – ‘more money for health; more health for the money’ as someone once said. Charles Clift has an interesting take on this:

“The WHO’s problem is not inadequate income. Rather, it is the imbalance between what member states, through the governing bodies, and voluntary contributors (including member states), through separate agreements, ask the WHO to do”.

He’s wrong of course: it’s not an either/or. The problem is that the WHO has inadequate income and that tied aid from MS and NSAs pull the organization in all directions.

In such circumstances, who’d want to be in WHO’s shoes?

The above article is compiled with contributions from; Linda Markova (UK), Kriti Shukla (India), Natasha Matthews (UK), Simrin Kafle (Nepal), Dan Owalla (Kenya), Emmanuel Tangumonkem (Cameroon), Alba Lop Girones (Spain), Matheus Falco (Brazil), Sophie Gepp (Germany/UK), Sherif Olanrewaju (Nigeria), Andrew Harmer (UK) and Ana Vračar (Croatia).